RESIDENCY REPORT FROM BAMBOO CURTAIN STUDIO, TAIWAN

BY VERONICA FRENNING

Report by Veronica Frenning, RU outbound artist in residency, during her stay at Bamboo Curtain Studio (BCS), Taiwan

Through my affiliation to Residency Unlimited in New York, I was selected to spend a month at the Bamboo Curtain Studio in November 2011.

Through my affiliation to Residency Unlimited in New York, I was selected to spend a month at the Bamboo Curtain Studio in November 2011.

http://bambooculture.com/en/residentartist/413

I spent a month at the Bamboo Curtain Studio (Taiwan) in November 2011. It is located in Zhuwei, New Taipei, surrounded by a mountainous landscape along the Danshui River. Bamboo Curtain Studio (BCS) encourages cross-cultural exchange and can accommodate multiple artists at once. During the time I was in residence, there were other artists working there from Sardinia, Hong Kong, California, and an aboriginal performer from the Ami tribe in Taiwan.

The buildings at BCS have been converted from abandoned chicken barns to live/work studios, offices and exhibition spaces. My living quarters were connected to a spacious private workspace. My proposal involved keeping a daily record of the state of working and of the work itself- through sculptures, drawings, collages, photographs and notations.

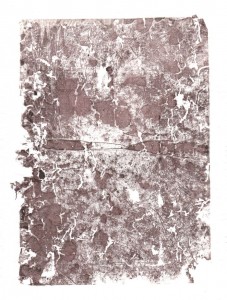

My most vivid impressions of Taipei were developed through exploring local flea markets, second hand markets, and night markets. I became fascinated with items that create a type of collective memory such as old hand tools, outdated and historical maps, castoff ink stones, and anonymous postcards from long ago. These findings became the starting point for my work there. It seems that most Taiwanese do not want “used or second hand items” and prefer to purchase new things. Many second-hand markets were difficult to locate (under bridges outside of the city center). At one place, I came across an old book (from the Japanese occupation period in Taiwan) that had been ravaged by bookworms. This particular book, it’s partial translation, and distressed condition, informed the idea for the first work I made. At various museums, shops and sites there are these inked stamps that relate to the location and name of the place. It is a popular activity there to take a stamped imprint in a notebook as a souvenir. Then by chance, during a visit to the Institute of History and Philology, I read about this technique called “full-surface rubbing”, which copied the entire shape and design of vessels before photography was invented. I was particularly intrigued by the images where the original vessel was lost, so now only the rubbing exists as a recording. Thus I could approach this found book as the “object” which I would document through methods of rubbing and transferring. A suite of prints emerged as a record of this object, although it was no longer recognizable as the original.

A substantial portion of my time was spent acquiring visual information from the outer surroundings, documenting it, and bringing it back to the studio. It was crucial that the source material for my work be culled from the exploration of Taiwan. Finding one’s way in an unfamiliar place and starting to recognize certain signposts became an everyday activity. As I would make return trips to an area, I would observe new things and take note of the differences and similarities, which became part of my daily practice. My camera pointed at a quotidian spider web, a stacked crate or a laundry line, which often seemed to create a mixture of curiosity and humor to passersby. The photos became a way to engage in a conversation with locals, and when the language barrier was apparent, I would simply playback the images I had captured to the curious individual. I wondered if he or she might appreciate something in a new way- since I too was gaining new insight into the culture- and in some respect, we were making an exchange in the span of a passing moment. These photographs, in a way, are a digital rubbing of an event, a condition, or object.

A substantial portion of my time was spent acquiring visual information from the outer surroundings, documenting it, and bringing it back to the studio. It was crucial that the source material for my work be culled from the exploration of Taiwan. Finding one’s way in an unfamiliar place and starting to recognize certain signposts became an everyday activity. As I would make return trips to an area, I would observe new things and take note of the differences and similarities, which became part of my daily practice. My camera pointed at a quotidian spider web, a stacked crate or a laundry line, which often seemed to create a mixture of curiosity and humor to passersby. The photos became a way to engage in a conversation with locals, and when the language barrier was apparent, I would simply playback the images I had captured to the curious individual. I wondered if he or she might appreciate something in a new way- since I too was gaining new insight into the culture- and in some respect, we were making an exchange in the span of a passing moment. These photographs, in a way, are a digital rubbing of an event, a condition, or object.

I arrived at BCS with the intention of working in clay but it proved logistically difficult. It became apparent that using readily available materials (as well as those possessing an ease of portability) would be a more pragmatic approach. So in conjunction with my photo documentation, I began to amass a collection of objects- some mundane as rocks, and others as unique as the Japanese ledger book. As my studio filled with these things during the residency, I began to reassemble them into particular relational compositions. These would be continuously re-worked as new matter was discovered, sometimes documented, and then even discarded. What slowly began to emerge was a method of form making and marking that explored the liminality between memento and art object.

The slippage between context and syntax of the sculptures (and the other parts of my work) were further explored when I projected these photographs at the open studio event. These photographic images served as a visual narrative, while the objects and works on paper were another type of residue in my attempt to record time in a place.

The slippage between context and syntax of the sculptures (and the other parts of my work) were further explored when I projected these photographs at the open studio event. These photographic images served as a visual narrative, while the objects and works on paper were another type of residue in my attempt to record time in a place.