Author: Michele Chan

Why are Taiwanese artists pioneering so many socially and environmentally engaged projects?

Art Radar investigates the trend, spotlighting two exhibitions of 12 quietly revolutionary projects that dynamically engage with social and environmental concerns.

From 3 July to 6 September 2015 the Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art (CFCCA) in Manchester, England, is presenting “Micro Micro Revolution” (2015), an immersive, interactive exhibition celebrating three socially-engaged art projects led by Taiwanese artists. Among its artists is Huang Po-Chih, who on 25 June 2015 was named on the shortlist of the HUGO BOSS ASIA ART: Award for Emerging Artists 2015.

At the same time, and on the other side of the planet, “Paradise – Sustainable Oceans” (2015) is an international environmental art project taking place in Keelung, Taiwan, until the end of August 2015. “Paradise” showcases nine site-specific outdoor sculptures and installations created by artists from Taiwan and around the world over a 25-day residency. This comes just after the Cheng Long Wetlands International Environmental Art Project was launched in Taiwan on 1 May 2015.

“Micro Micro Revolution”

“Micro Micro Revolution” at the CFCCA in Manchester is being curated by Taiwanese curator Lu Pei-Yi. The show explores the “power of art as a vehicle to address social change in Taiwan”. The three projects, entitled A Cultural Action at the Plum Tree Creek, Plant-Matter Needed and 500 Lemon Trees, address pertinent issues such as land-use, pollution and sustainability. The projects are ongoing, process-based and participative – actively using art as a form of resistance and a platform for exchange.

A Cultural Action at the Plum Tree Creek was initiated by artist Wu Mali and the Bamboo Curtain Studio in 2010. The project brings together schools, universities and community groups in Taipei to reconnect with Plum Tree Creek, located in the margin of the Taipei basin and the mouth of the Danshui River. The water in the creek is heavily polluted, in some places diverted, drained or covered. The project encourages affected communities who rely upon the river to reclaim ownership over their natural resource and care for it through art, education, research and collaborative action.

Plant Matter Needed: The Material World of the Riverbank Amis Tribe 2015 was initiated by artists Hsu Su-Chen (1966-2013) and Lu Chien-Ming. In 2009 the Sa’owac Village located in Dahan Creek faced the threat of demolition due to a new urban development plan for a riverside cycling route. Hsu and Lu collaborated with the local community to protest the plan and rebuild their settlement, bringing to attention issues such as living rights, environmental concerns and the marginal status of aboriginal people in north Taiwan.

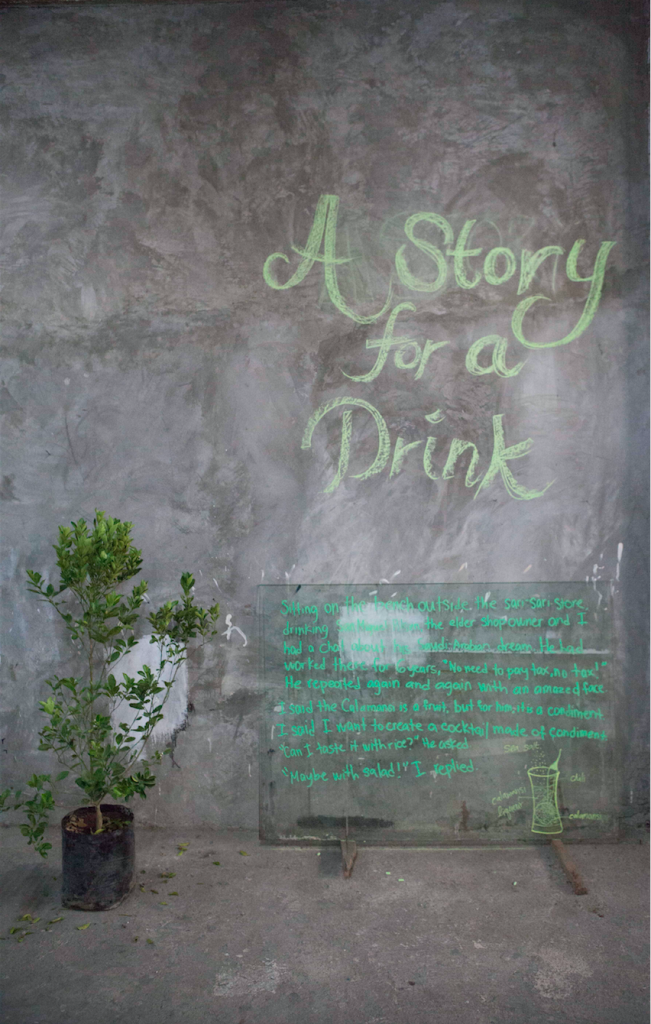

The third project, 500 Lemon Trees, is by the critically-acclaimed, emerging artist Huang Po-Chih. Huang is responsible for the temporary orchard of lemon trees at the CFCCA space in Manchester. For his project, the artist set out to regenerate three abandoned farmlands in Taiwan that had been neglected for 20 years, asking 500 participants to each donate TWD500 to buy a wine label. The sale of each label funded the planting of a lemon tree in the farmlands – and two years later each participant received a bottle of Limoncello. The press release explains:

The project re-establishes both enterprise and art production as methodologies for sustainable social change, reigniting the relationship between farmers, their land and business practice.

The soft power of social engagement

Lu Pei-Yi, Associate Curator of the CFCCA, hails from Taiwan and primarily specialises in the area of socially-engaged art. Speaking to Art Radar about the exhibition, she explains the concept of a “micro” revolution:

Rather than taking a provocative position on social issues, I would like to present another approach to UK audiences: a soft strategy, eco-friendly attitude that might be rooted in the culture of respecting nature in spirit. The repetition of “Micro” [in the exhibition title] emphasises that this small, soft power still has the potential to trigger a revolution.

Lu goes on to talk about an important aspect of socially-engaged art – the interaction with audiences and the dialogue born from exchange between different cultures. The power of such projects stems precisely from its ability to raise awareness, invite discussion and ultimately incite action:

These three projects are all long-term, process-based, and participative and have tangible and important impacts on their local communities. Impacts we hope to transcend to wider society [...] My idea is that socially-engaged art is about people. Rather than curating another “documentation” show I was keen to have artists on site to talk to people and to instigate dialogues and discussions between cultures.

“Paradise – Sustainable Oceans”

On the other side of the world, “Paradise” focuses on the marine environment and is currently on show at the National Museum of Marine Science & Technology (NMMST) in Keelung. It is being spearheaded by Art Radar correspondent and veteran environmental art curator Jane Ingram Allen.

In contrast to “Micro Micro Revolution”, which focuses on process-based actions, “Paradise” features actual objects, showcasing nine site-specific sculptures and installations created by artists from Taiwan, India, Indonesia, the United States, the United Kingdom, Italy, Germany and Ukraine.

As the press release explains, the island of Taiwan was originally called ‘Formosa’, meaning ‘beautiful island’, by the Portuguese explorers who first arrived in 1544. Located in the fishing village of Badouzi on Taiwan’s northeast coast, the NMMST is situated in an area that still “retains [...] a feeling of paradise even in this time of ocean acidification, global warming and increasing pollution”. Artists from around the world were invited to create site-specific, sculptural installations. Using only natural and recycled materials, the works aim to raise awareness about protecting and conserving the marine environment.

Three out of the nine artists are Taiwanese, including Chris Kuei-chih Lee, Yi-Chun Lo, and Hung-Wei Lin. Utilising driftwood, sisal rope, recycled fishing nets, wooden rods and recycled chopsticks, Lee’s Exiled Reef (2015) reminds us about endangered coral reefs in the world’s oceans. Lo’s multi-colored, solar-powered Gift of Light allows visitors to walk under a mesmerising rooftop made of bamboo and recycled glass bottles. Lin’s Octopus Gathering (2015) is a multi-part installation created with the involvement of local high school students.

Taiwan’s environmental consciousness

Why is Taiwan pioneering such projects? Lu Pei-Yi points out that Taiwan has a strong legacy of an environmental consciousness. She cites the environmental social movement of the 1980s as one that contributed significantly to political reform and the lifting of the martial law in 1987. According to Lu, in recent decades many young Taiwanese people have returned to their hometowns to work on organic cultural projects.

Jane Ingram Allen also notes that being an island surrounded by the sea, Taiwan may be facing rising waters, global warming and other effects of climate change more immediately than other parts of the world. It is perhaps this – as well as changes in the country’s social fabric – that are making Taiwanese people more concerned about the environment. As Allen says:

Now there is also less pressure to keep industrialising and building more polluting industries, and people can begin to think more about the quality of life and the future of their country. I think that in the cycle of life for countries and civilisations, environmental concerns are ignored and neglected usually until the basic needs are met and the economy developed enough to give people time to think about other things such as the quality of the air, water, soil and so on.

The future of Taiwan’s ecological revolutions

Both Lu and Allen believe that environmental art is a growing trend and that awareness is increasing. Allen states that although it is a slow-building process, environmental art is “a softer way to bring attention to environmental issues”. As she says:

I think more scientists and science museums are starting to see that artists can also help and that artists can speak with a different voice and make unique contributions to the discussion about what to do about the environment.